“And don’t think the garden loses its ecstasy in winter. It’s quiet, but the roots are down there riotous.”

What is “meaningful rest?” In a culture that encourages – and often demands – that we burn the candle at both ends, sacrificing our wellbeing for the pursuit of greater and greater productivity, rest is both an essential and transformative act. For those of us who practice magic, rest and sleep can become as integral a part of our craft as anything we do in our waking lives. Sleep can be medicine. Dreams can aid us in divination. A peaceful night of restorative sleep – or a power-nap to pull you through a strenuous day – can recharge our body, mind, and spirit. Meanwhile, waking activities that ground us in the present moment or simply allow us a break from exhausting cycles, are, in their own way, restful. More and more, resting with purpose is part of my work, and allows me to connect more deeply to the rhythms of the natural world.

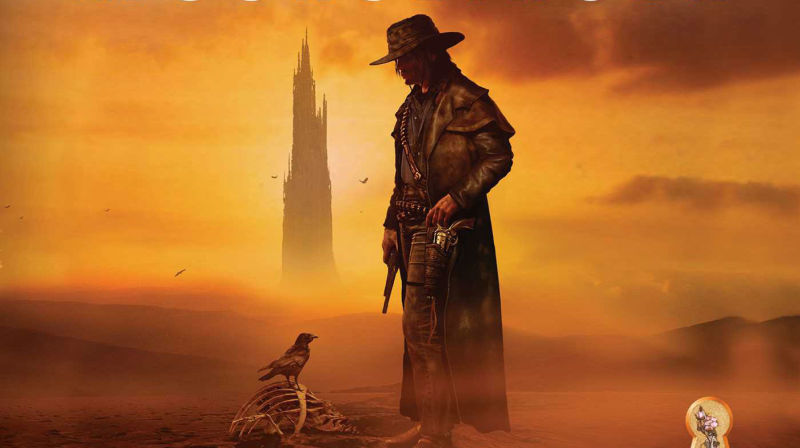

January marches on, and I am deep in my winter cocoon. I live in Philadelphia, and just days ago, the region saw its first significant snowfall in two years; looking out the window as I write this, I can see the blankets of fresh snow crystallizing and solidifying on rooftops and sidewalks. This atmosphere, combined with the exhaustion brought about by the winter holidays, has me yearning to curl up with blankets, tea, and books around the clock. These January days feel, to me, like a long, slow exhale – a release of the excitement and energy of the end of the previous year. But at the bottom of every exhale, we breathe in again, and the natural world provides us with cyclical cues that can augment our own cycles. In my work, spiritual practice, and personal life, these cues align with the eightfold Wheel of the Year: the cycle of seasonal festivals and sabbats observed by many pagan and earth-centered spiritual traditions.

The four solar festivals (solstices and equinoxes) are bridged by seasonal celebrations that correspond with the changing characteristics of the natural world and the harvests. Because this framework is presented as a wheel, there is, naturally, no beginning or end. The Wheel of the Year is a modern framework of observances, though its origins run deep in history. Each festival carries its own folklore and customs, which can aid us in aligning deeper with the rhythms of the natural world.

Deep in the snowy corridors of January, we are approaching Imbolc, which heralds the coming of spring. Just as the bulbs below ground need a freeze to prepare themselves for regrowth in the spring, we need this time for wintering, recovering, regenerating. As the year revolves, repeating its cycles with tradition and variation, we can look to the earth’s cues to build cycles of activity and restorative rest into our lives. The plants, animals, weather patterns, and harvests remind us that resting is part of the work we do; it is essential, and it is transformative.

Imbolc: Observed on or around February 1, halfway between the winter solstice and spring equinox. Though Imbolc occurs during the coldest time of the year for most countries in the Northern Hemisphere, it is seen as the gateway to spring. Snowdrops are among the first flowers to appear. Shortly thereafter, the earth begins to soften and flower again. This is a time for gentle stirring below the frosted soil; a long, slow exhale for us after the excitement of the winter holidays.

Ostara: Observed in accordance with the vernal (or spring) equinox. Ostara frequently coincides with the Christian celebration of Easter, and both share symbolism of eggs, rebirth, and rabbits. At this time, the earth sits in a delicate balance between day and night, winter and summer. Night and day occupy equal hours – a phenomenon that only occurs in the spring and the fall. On either side of the equinox lay extremes, but at the height of transition, a cosmic alchemy emerges. This is a transitive moment – the bottom of the exhale, as we prepare to increase our activity again.

Beltane: Observed on or around May 1, or when the hawthorn (May) tree begins to bloom with abundant mayflowers. Beltane welcomes the transition from spring to summer. Situated opposite Samhain on the Wheel of the Year, it is a time when the veil between worlds is thin. In these days of increasing light, we may linger longer outside, dance around bonfires, and enjoy the twilit beauty of our surroundings.

Litha: Observed at or near the summer solstice (June 21 in the Northern Hemisphere, or December 21 in the Southern Hemisphere). This sacred fire festival, sometimes recognized as Midsummer, marks the longest day of the year. But even at this time of peak sun, the earth prepares to turn toward darkness. We cling to the brilliant summer sunsets, the warm ocean waves, the pleasant exhaustion of bodies at play, knowing we now face the darker, more withdrawn half of the year.

Lughnasadh/Lammas: This seasonal festival, observed on or around August 1, marks the start of the harvest season with the grain harvest. At this time, we celebrate abundance with games and dancing, but there’s a solemnity to this harvest as well. We offer up the first grains to our gods and goddesses, and we bid farewell to Persephone, who begins her journey to the Underworld.

Mabon: Observed at the autumn equinox when the night and day occupy equal hours. Marking the second harvest festival, Mabon is a time for giving thanks at the height of autumn.

Samhain: Observed around November 1, and coinciding with secular Halloween festivities, Samhain is the final harvest festival. As the skies darken and leaves fall, it’s a time to honor our loved ones who have passed beyond the veil.

Yule: Observed at the time of the winter solstice (December 21 in the Northern Hemisphere, and June 21 in the Southern). On the shortest day of the year, the Oak King wins the battle against his brother the Holly King, and the earth, emerging from darkness, moves once more toward light.

It’s especially in the darker months that I reach for reminders to rest. Though many of the sabbats or seasonal festivals correlate historically to harvests – times of intense labor – this is also the time that the natural world is slowing down. Dropping its leaves, settling under a layer of frost. The sun itself takes longer and longer naps, if you will. And as all this is happening, and incredible network of essential activity is happening beneath the soil. This year, as the Wheel turns, let’s endeavor to be like the riotous roots down there. Let’s dig deep, soak up all the nutrients we need without feeling guilty, and prepare to flower.

Looking to connect more deeply with the Wheel of the Year? Sea Witch Botanicals creates handcrafted incense and home goods inspired by the natural world and the seasonal festivals. The Wheel of the Year Incense Gift Set includes a signature all-natural incense for each sabbat, the perfect tool for living more in tune with the seasons through a complete calendar year. Each incense lets you celebrate the bounty and beauty of each new season, or harken back to seasons past whenever you please.

Through February 5, use my code WINTERNAP for 15% off your order from Sea Witch Botanicals.

Laurel Hostak Jones is the author of Sleep & Sorcery: Enchanting Bedtime Stories, Rituals, and Spells, now available from Crossed Crow Books.